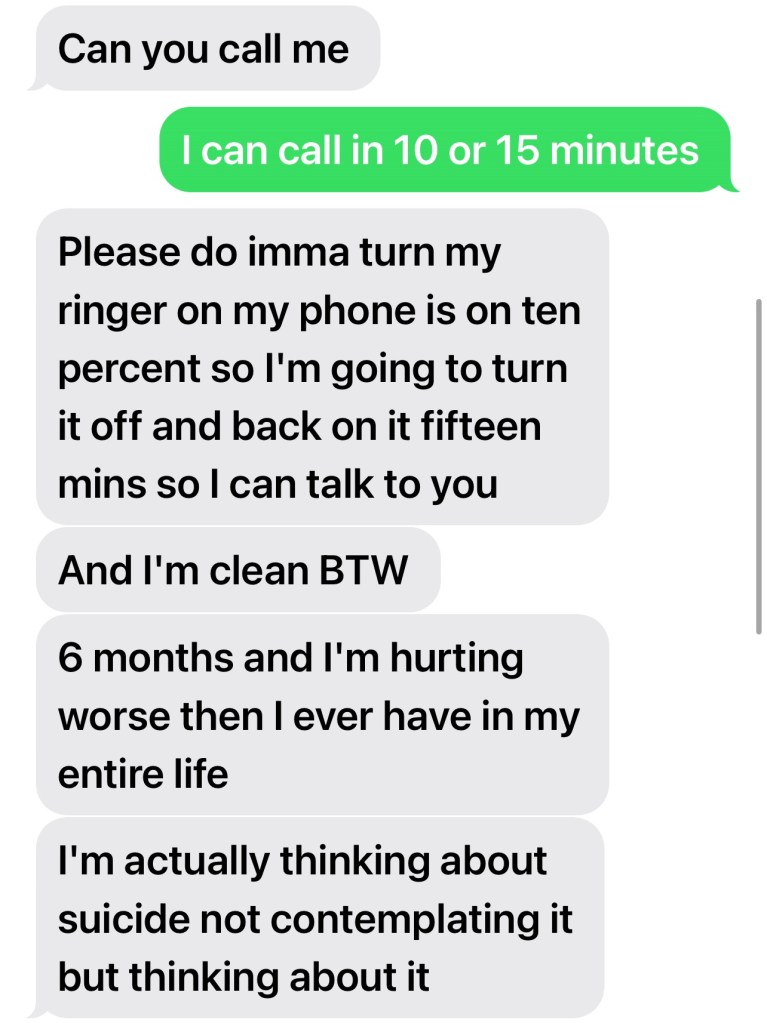

I started photographing in New York City after a two year lay off. I had completely lost track of Little Bit, and our lives had gone on completely separate paths. I never thought I’d see her again, and I had no intention of seeking her out on the street. Not because of negative feelings toward her (I will always care deeply about Little Bit and what happens to her), but because of my own cynical, bleak views concerning photographs of addicted, homeless or otherwise tormented people.

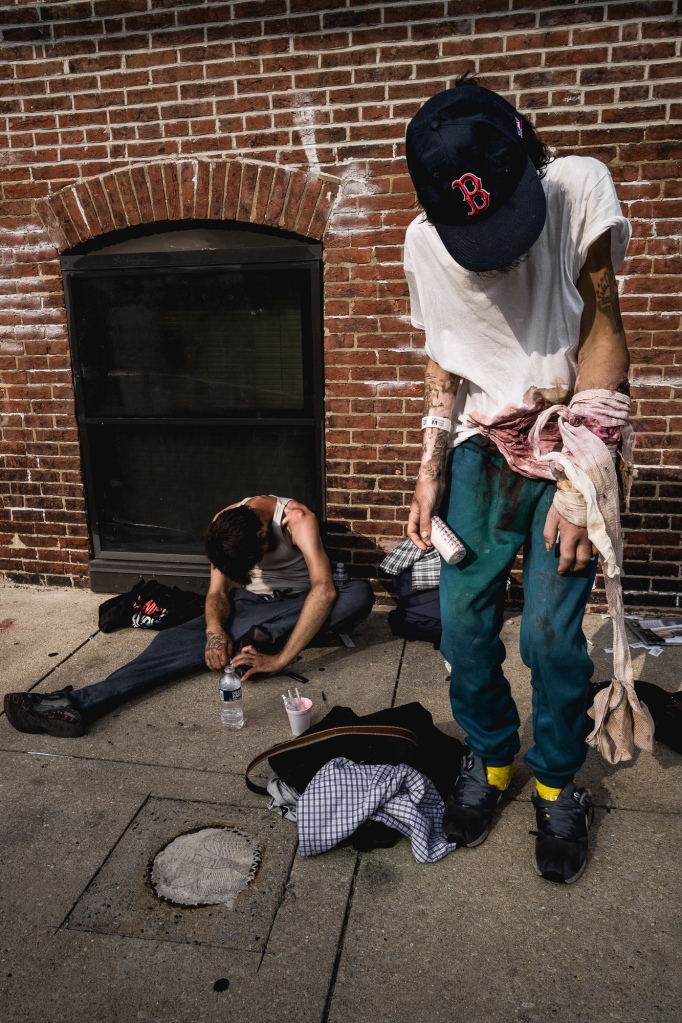

Photographing in Kensington, Philadelphia for three years has changed everything about the way I perceive my conduct as an image maker. My feelings about photojournalism and street photography generally—more specifically how it’s practiced by others—are completely separate from my expectations of myself, my personal standards and methods. After being shot at, assaulted and beaten on the street and generally being forced to fight for much of my output while in Kensington, shooting pictures in New York City as a street photographer is too easy. Of course I get into altercations over my right to photograph, what I’m doing, why….but it’s a pale comparison to Kensington, or any place that’s close to it in tension and gravity, a war zone, conflicted places that require much work in order to effectively photograph .

I will always love photographing the street, but lately I worry that I no longer find any relevance or meaningful content in walking the same footpath I’ve been on for so long.

If I can tell a story, I hope I will always be inclined to pick up my camera and try. It’s not always successful but making the effort is what makes me happy. What is discouraging for me is that, after Kensington and so many other stories I have told…I sometimes see the streets as being vacuous and devoid of any kind of purpose.

Lately I see so many out with a camera….like shopping before a holiday. Looking up, finding someone watching me, camera in hand, on the same corner. I find myself feeling like an intruder, poaching innocent people out there trying to get from place to place. I see what I am doing differently sometimes when I observe others with a camera. I wonder how we look to passerby. I never cared…never once considered that what I was doing was odd or unusual. But at times lately I wonder if much of street/reportage/documentary work is in fact outright predatory.

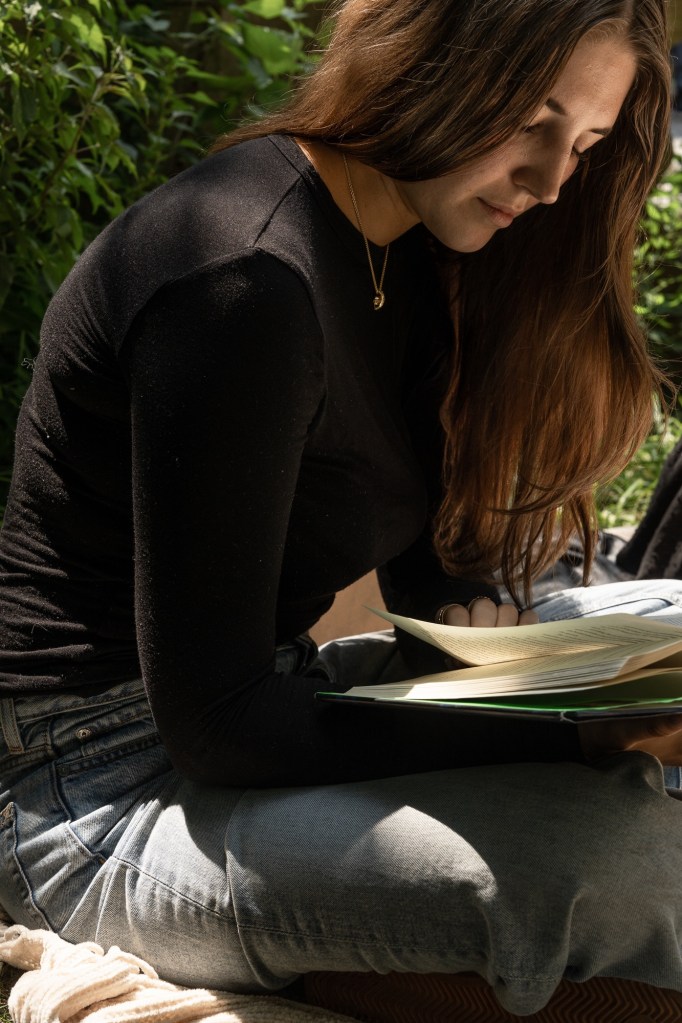

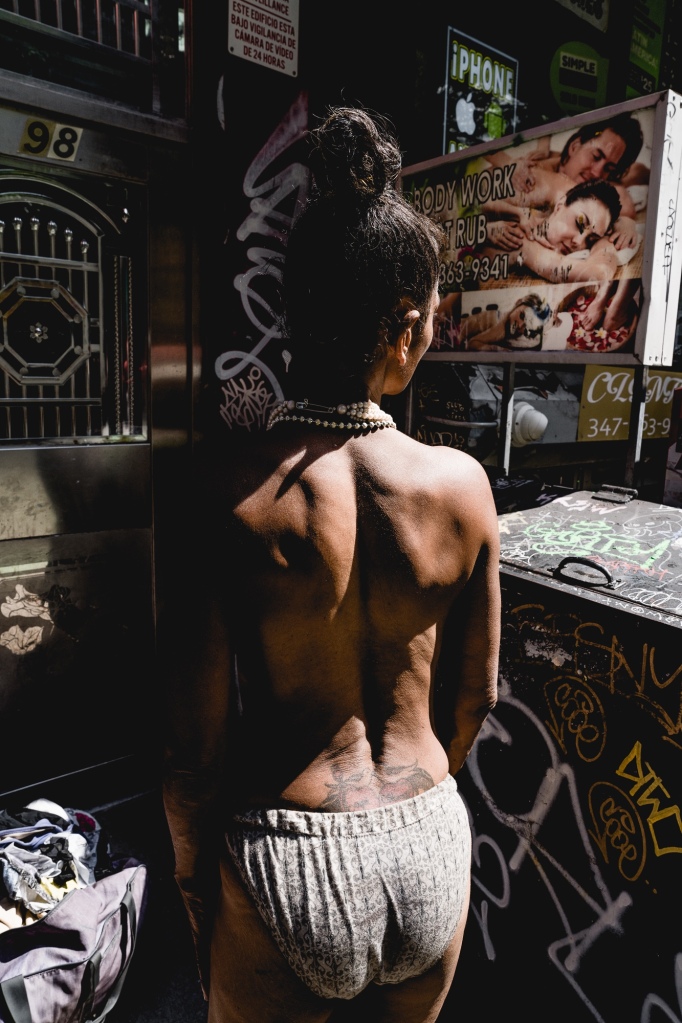

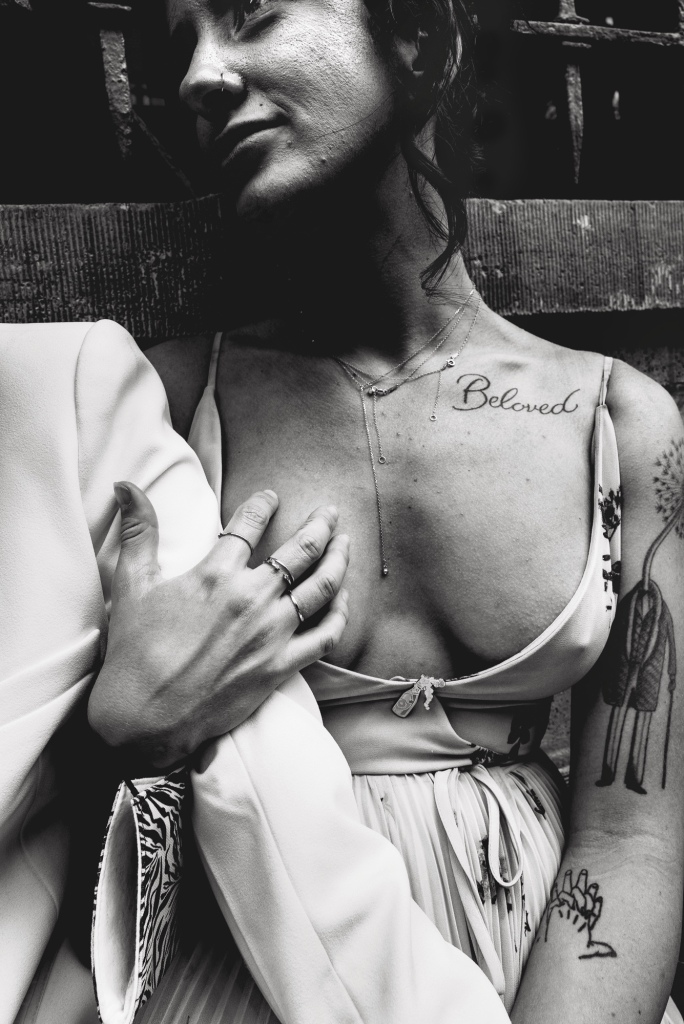

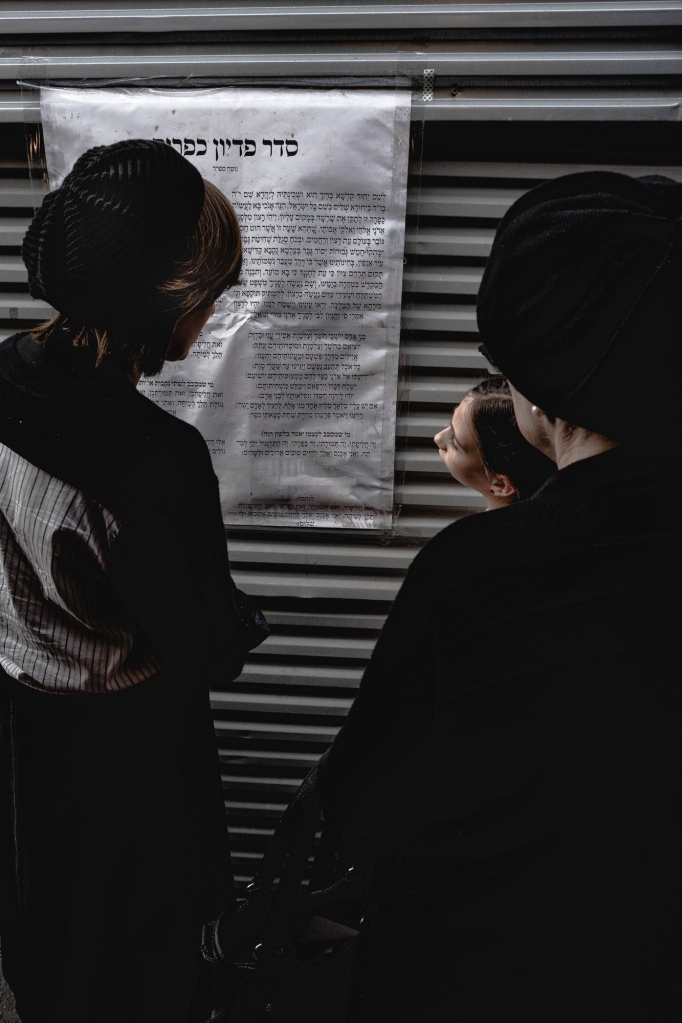

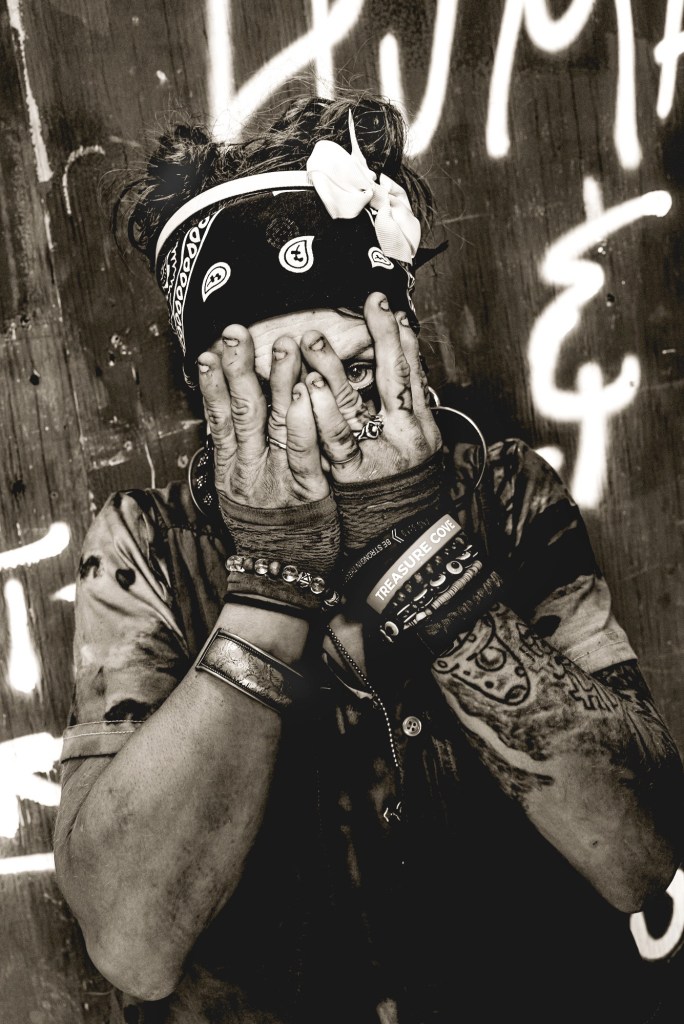

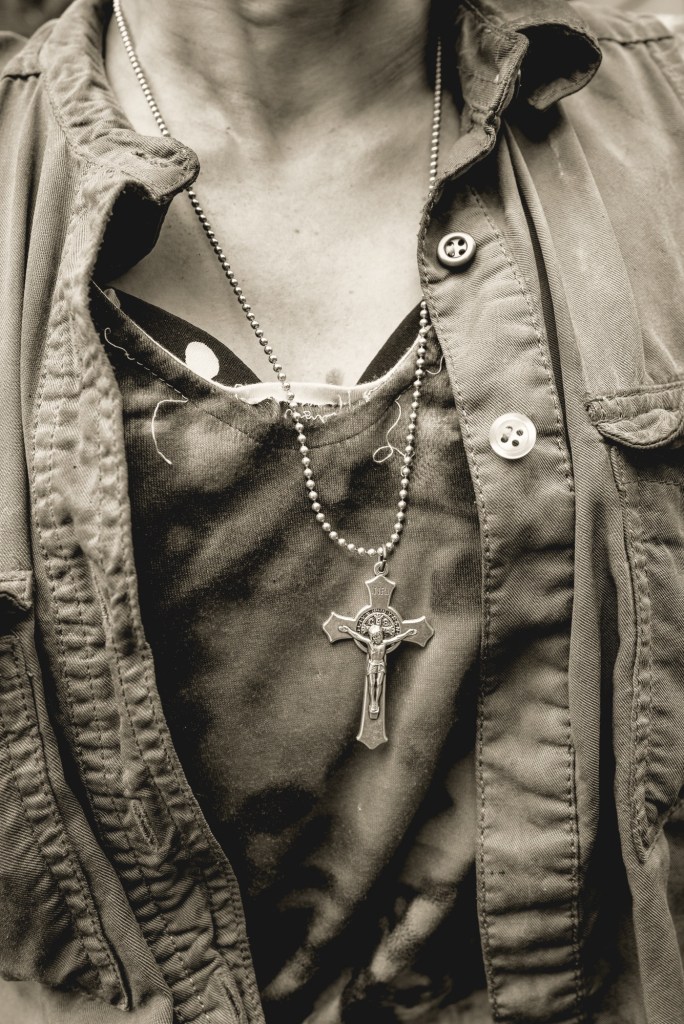

The images above are some of my favorites….sights that motivate me even as I look at them now…pictures that make me resist the urge to give up on photographing people.

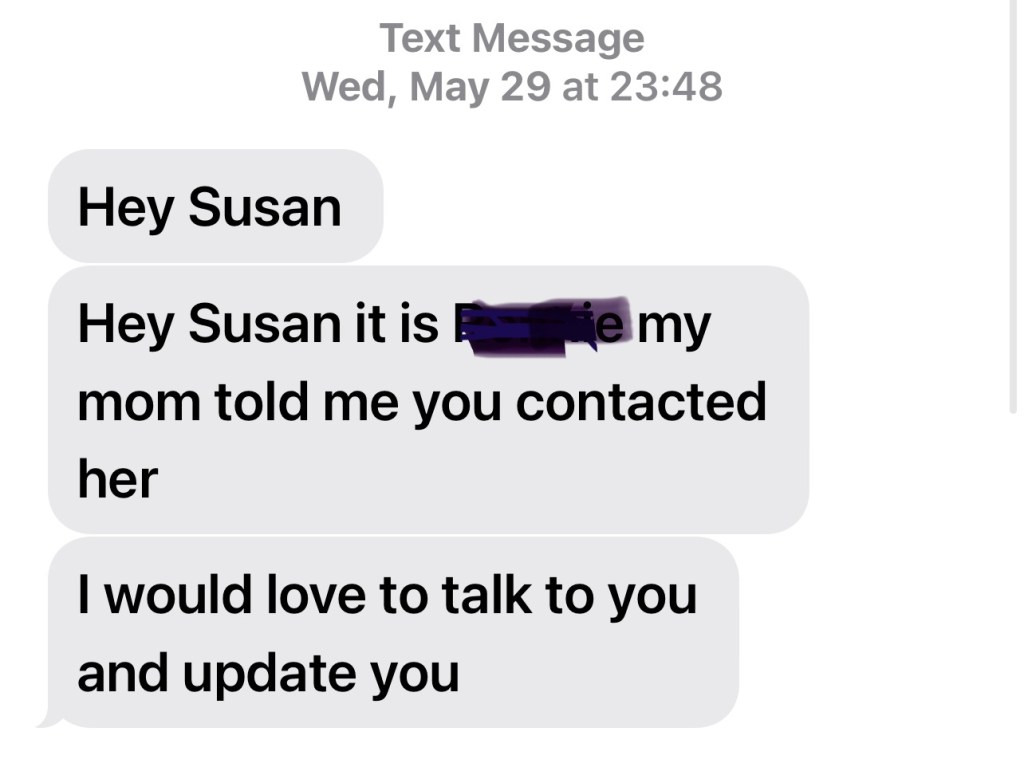

I ran into Little Bit after two years. I thought if I saw her, I would not have any desire to photograph her, but I was wrong. The urge came back fast, as did my connection to her. I had been walking down the street, on my way to a camera store. I spotted a miniature, colorful umbrella hunched against the side of a storefront. A pint sized encampment. I realized that it had to be her…tiny Little Bit at last.

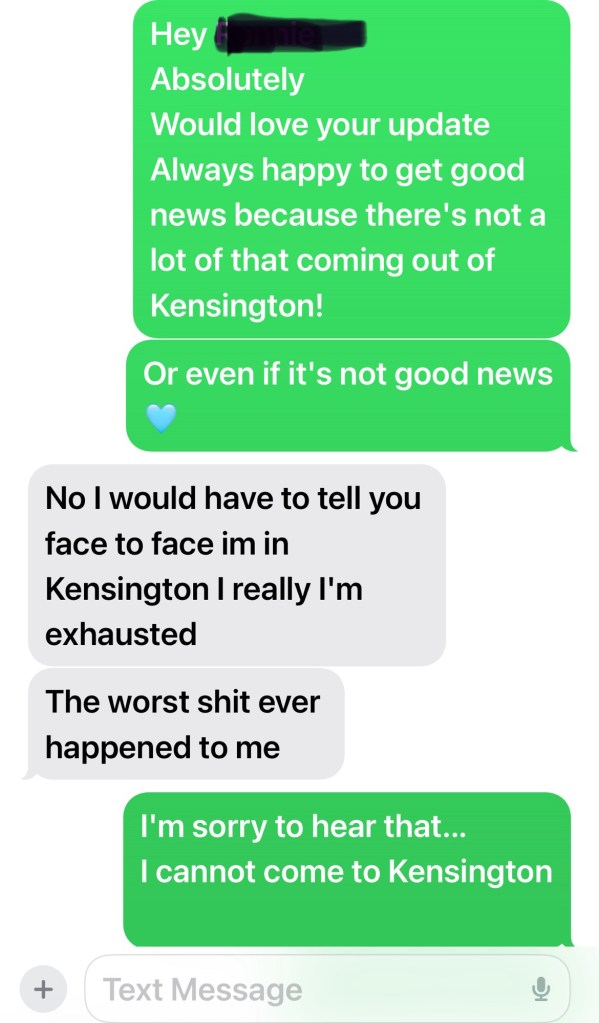

As we crossed 6th Avenue, we were photographed together by a street photographer who suddenly picked up her camera when she realized that it was me with Little Bit. This upset Little Bit as she made her way along the crosswalk. I felt that my work, spanning a period of six years, had created visibility, a public persona for her, an excuse for people on the street with cameras to feel justified in acts of intrusive picture taking. Pictures that are not documents, or legitimate moments of life in public spaces. Pictures that are purely exploitative, unimaginative and irrelevant. I sometimes run across imitations of my work with particular people that I had never anticipated and feel very uncomfortable with, especially when I have personally witnessed photographers exhibit stalking behavior and had to advocate on the spot for the privacy of someone who has allowed me the privilege of photographing them. I have felt genuine shame when some of my subjects have related to me incidents of people with cameras secretively photographing, or approaching them at odd times.

Social media has made original work constantly accessible, and impossible for me and other artists in a similar situation to protect. Style, subject matter, location, entire bodies of work, compositional techniques….easily available to others and open to exploitation. Where is the line that separates artistic influence from copying the work of other photographers and plagiarism? A thin, almost nonexistent difference on social media. Most of the time I don’t think about it but there are times when it’s a problem that almost negates the positives associated with social media engagement.

We walked for hours, and it was like no time had come and gone. We had ice cream, and I found out that she had left the shelter she had been living in for nearly four years. She was not regretful. Little Bit has chosen her life, and resists victimization. She is in control and is remarkably able to avoid being abused by people on the street most of the time. But Little Bit is not able to avoid being abused by the rest of us, especially those with cameras.

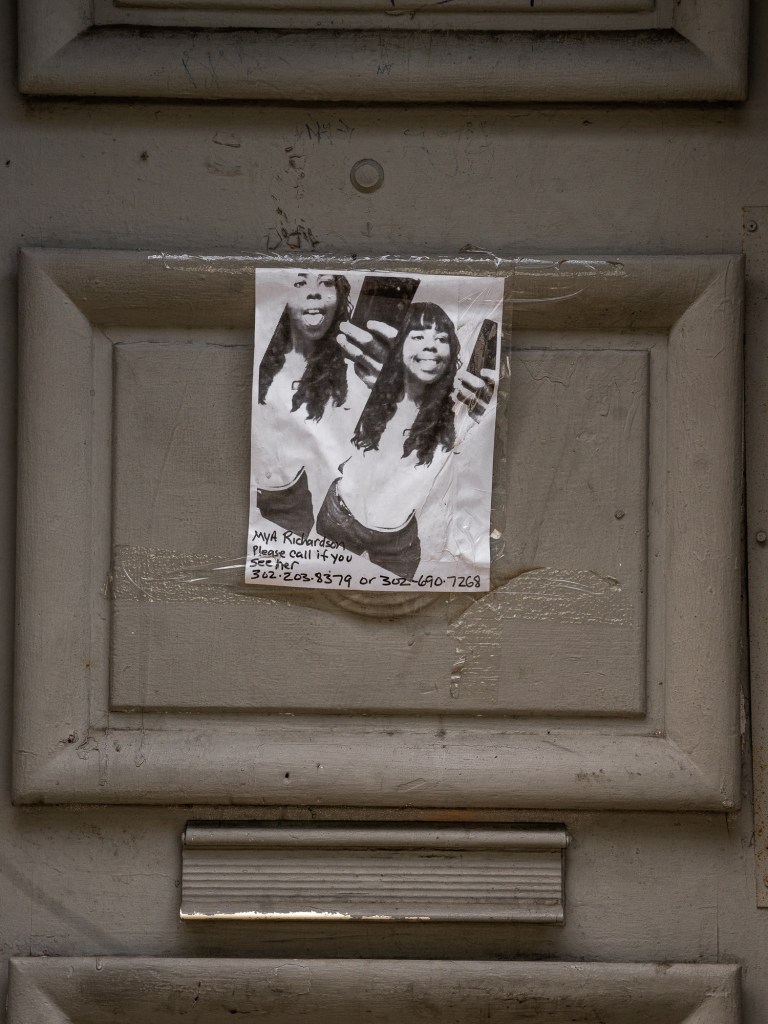

No less than three people made iPhone videos of her while we walked. Little Bit became angry and startled by the intrusions. She explained that a TikTok “creator” had made a video a year or two ago….I explained that a lot of people have seen my pictures of her as well. I know that my images have inspired others to seek her out, and I am deeply concerned and sorry for the negative impact. When people ask her politely for a picture, she sometimes allows herself to be photographed. But she doesn’t truly feel comfortable with the process. Because I spent time with her, after a long period she came to trust me, becoming comfortable with me taking pictures of her many incarnations. She has been extraordinarily generous with her likeness.

Little Bit is a lifelong amputee, and this disability has made her a commodity at times on the street. I could see, however, that she had become an easy target for some without the skill or sensitivity to approach and effectively manage photography of difficult subjects like Little Bit. A harsh statement to be sure, but a truthful one.

In the future I will no longer give location information for some of my work if it can negatively impact anyone in the image. Every day I wonder if what I am doing has any significance, and sometimes it’s a struggle to pick up my camera, even to drag my feet along as I move forward. I don’t ever want to feel that my satisfaction with my work somehow degrades another person….but I now know that in documenting difficult circumstances it has done just that. It’s unavoidable, and unacceptable at the same time. Unavoidable because to walk away from difficult situations, not photographing the way things really are, is an acquiescence to present day forms of censorship. Unacceptable because causing pain is never ethical….but justified because there’s a perception of a greater good. Documents of truth and life no matter how hard they are to look at or acknowledge I feel is the best path towards durable, righteous journalism. I know that seeing my pictures has caused pain, and in showing life accurately there are casualties. The wounded in the image, and me too. I have come to realize that I too am a casualty of my photography. I’m not yet sure what that means for me.

Images and story told with Little Bit’s permission.