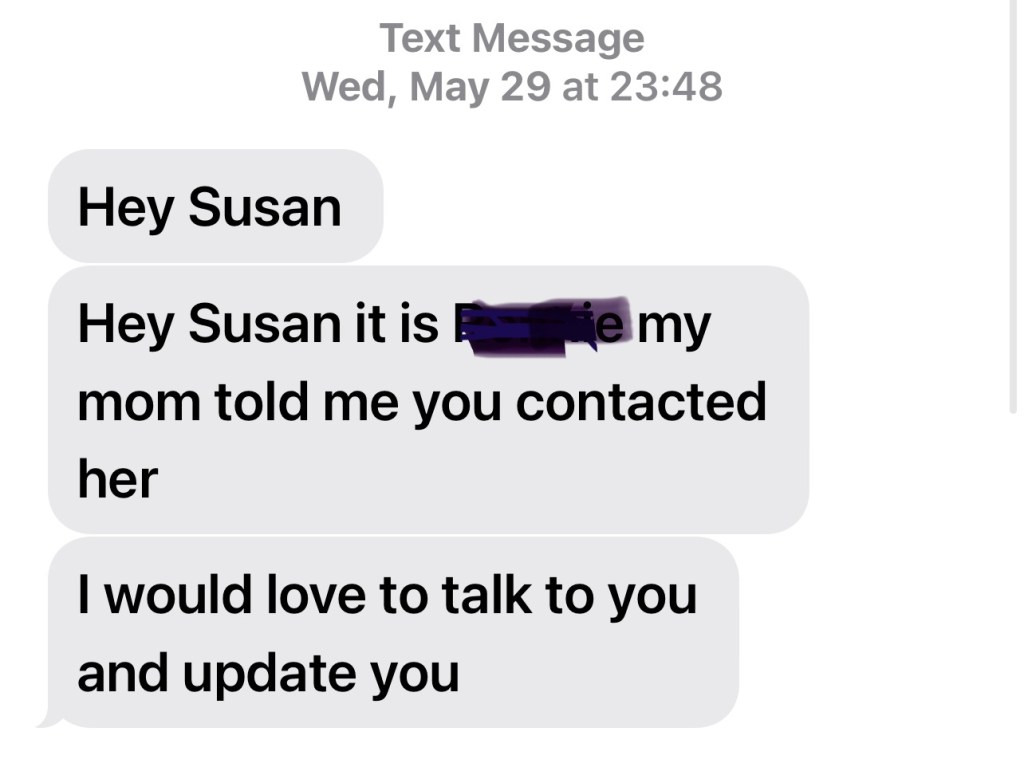

I give out my phone number. Not every day, and not to everyone I photograph or meet in Kensington. When I interact with someone that I think is especially vulnerable, or if they want me to send them pictures I have made with them, I give them my contact information so that I can text an image. Sometimes I have sent pictures via text to people’s parents, and then a parent of someone on the streets of Kensington will have my mobile number.

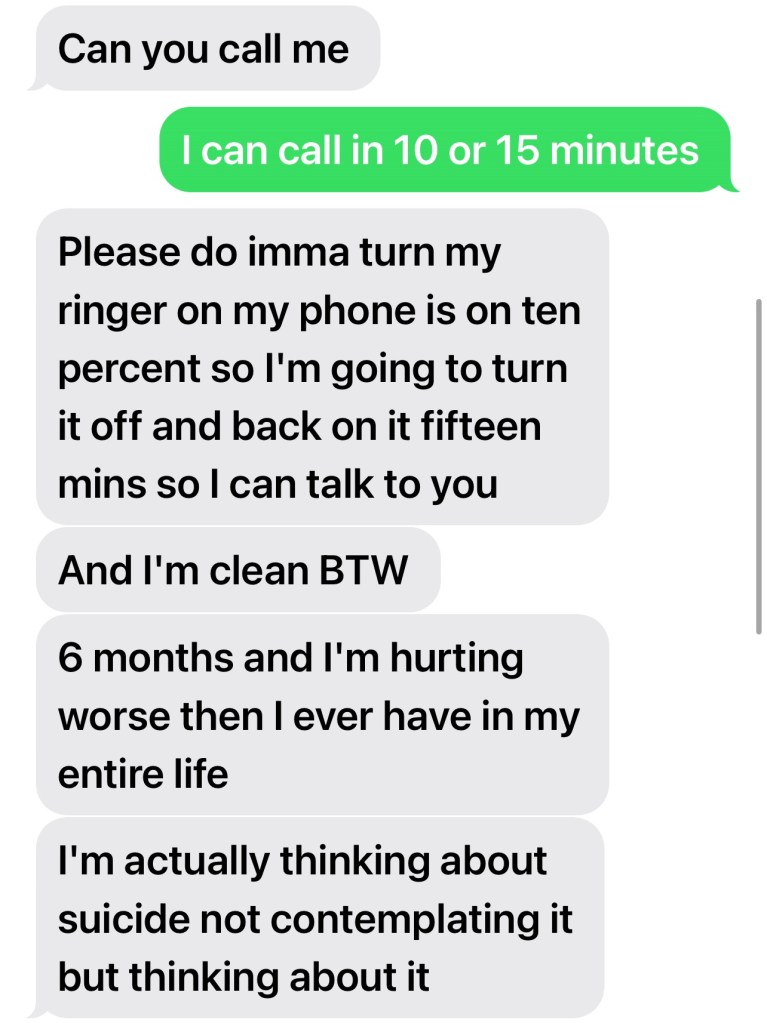

Giving out my personal phone number is a risk, but I often share it because I have always felt that it’s more important for me to be able to be within reach if someone is hungry, or needs a ride to the Emergency Department, or wants to talk. I’ve been doing this since I became a photographer, and in 8 years it’s only been abused a couple of times. I understand that it’s not an obligation as a documentary photographer….but shouldn’t it be? If I insert myself into a person’s sphere, one sometimes full of extreme emotion or calamity or precariousness, isn’t it fair to say that it’s morally correct to be available for a select group, one that I have taken care to document and advocate for? It becomes more of a responsibility than a typical 9-5 work day entails. Vulnerable people, in horrible situations. But in Kensington giving my contact information has allowed people to think that I am someone that is potentially a source of gain. Stuff in my car, in my camera bag, on my person.

When is it acceptable to consider a portrait of a life a never-to-be-repeated encounter whose responsibility ends when the last photo is taken? These images are sometimes burned into my soul. Learning to recognize that the experience that I have of the images and situations depicted and the intensity of the moments I am witness to does not mean that those experiences of mine—or the images created— reflect the deepest realities and truths of those that are in the images. At what point and with whom do you set a personal boundary? The sense of obligation that I often feel to try to offer aid to those in my images has in fact put me in jeopardy. But it has taken me a year and a half to fully understand how easy it is for trust to be abused, and how dangerous the simple act of texting a picture can be. Because Kensington is a very particular place, and I have learned that it has its own protocols and standards of behavior. One unwritten but universally recognized social norm on the streets of Kensington is that if you unintentionally open a door of any kind that could be used to exploit personal vulnerability—and acts of kindness or donation unfortunately fall into that category—one can be placed in a potentially dangerous situation down the line. Establishing trust with small gestures is only possible if both people have a similar understanding and respect for the delicacy inherent in the process of investing in someone else. Because gaining the trust necessary to be given contact information is itself a hustle that can pay off in the future.

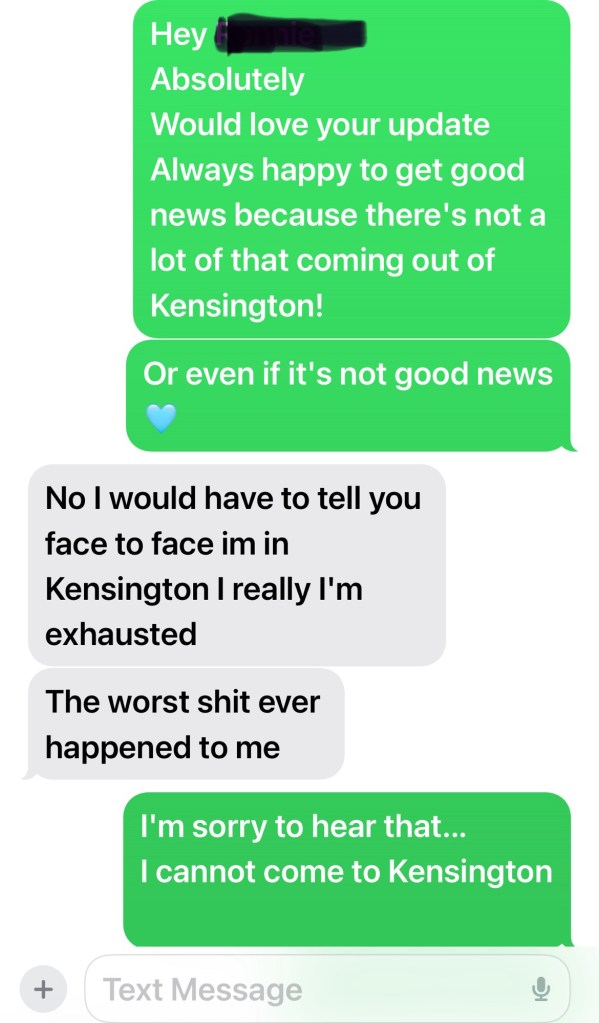

I’ve been set up several times in Kensington, by people I have gotten to know. Using my phone number to call or text to express urgency in order to lure me to a meeting place, where my equipment can be stolen.

Face to face meeting requests, especially when the sender is messaging or calling me at night, are an immediate warning. When someone expresses an urgency that they know has the potential to worry me, or to galvanize me to race to Kensington to act as savior is nearly always an attempt to bait me into showing up somewhere. And these requests can come from people that have been given food, or mobile phones, or other kinds of support and help. At first, I felt disappointment. Not in the person trying to deceive me, but in myself for being such an obvious mark. I realized that whatever conversation I had had with people was subterfuge. And I felt embarrassed. This has happened too often, and I’ve been forced to overlook these failings in those who I have documented in order to move on and keep documenting. A set up can be an act of violence or theft that could be awfully hard for me to come back from. And I have learned that the level of criminality and dysfunction in a population that I have at times grossly misunderstood and underestimated can sometimes rise to a level of seriously manipulative, destructive and sociopathic behavior. I have been deceived by this masquerade at times, mistaking it for a kind of hapless, childlike state of vulnerability, casualties of the ravages of accidental drug addiction and resulting trauma experienced while living on the streets. Which is sometimes the case….but not always. And it can be very hard—nearly impossible at times—to detect when there is deception or masquerade. An inability to recognize the signs of manipulation can be life altering.

In some places, any act of kindness can signal vulnerability, and even the smallest of gifts can invite exploitation. It’s a kind of entitlement that develops when even the act of saying thank you becomes a rarity and is a product of very low expectations and too many gifts given.

Learning when to believe in someone, and to resist the urge to blame everyone for the sins of a few is a most important skill. Walking away from a person who needs belief and support would be an unjustifiable tragedy.